Mamdani and MLK

A writerly look at a speech for the ages

Zohran Mamdani gave a remarkable speech on Tuesday night, declaring victory in the NYC mayoral race. It’s now my favorite speech of this century, both politically and rhetorically.

I’m a bit biased, because Mamdani borrowed some stylings from Martin Luther King. When I taught composition and essay writing, I would devote an entire week to “words meant to be heard, not read,” using King’s “I Have a Dream” as the centerpiece and speeches by Lincoln and FDR on the wings.

I wanted to go through the speech rhetorically for my own benefit, to make sure my initial impressions were sound, and because I would almost surely include this speech if I did a class on public speaking. Here’s what I found.

Sources

The video:

The transcript:

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/05/nyregion/mamdani-speech-transcript.html

Thank you, my friends. The sun may have set over our city this evening, but as Eugene Debs once said, “I can see the dawn of a better day for humanity.”

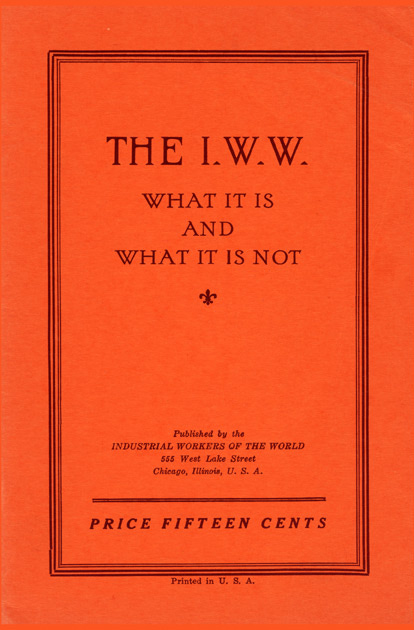

Debs was a turn-of-the-century union organizer who also helped found the Socialist Party of America (1901) and the Industrial Workers of the World (1905). It’s no accident that Mamdani starts his speech with a shout-out to him. Much has already been made of Mamdani using the word “socialist” in his self-description, but I don’t know that much has been written about his spiritual kinship with the I.W.W., nor is it an organization that the average person knows much about. Here’s something they wrote about themselves:

“Every day and every hour of every day, week after week, and month after month, year in and year out, the I. W. W. concerns itself solely with and about the wage relationship, which involves a constant struggle between employers and employees. It seeks and strives constantly to arouse the sentiment for a shorter work day among the wage workers. It endeavors to organize them to demand and secure shorter hours. It tries to organize the workers in an effort to secure higher living standards. It would organize the workers to obtain better and more healthful conditions.”

The I.W.W. was far more radical and progressive than other labor organizations of that era, and uniquely opposed to racism and sexism:

“Race color, religion, nationality, age or sex do not provide grounds upon which the I. W. W. will divide those whom the employing class have united industrially.”

For as long as we can remember, the working people of New York have been told by the wealthy and the well-connected that power does not belong in their hands.

Fingers bruised from lifting boxes on the warehouse floor, palms calloused from delivery bike handlebars, knuckles scarred with kitchen burns: These are not hands that have been allowed to hold power. And yet, over the last 12 months, you have dared to reach for something greater.

Writers know that specific images are more powerful than generalities. Given the right specific images, the listener will generalize on their own to what the writer wants them thinking about.

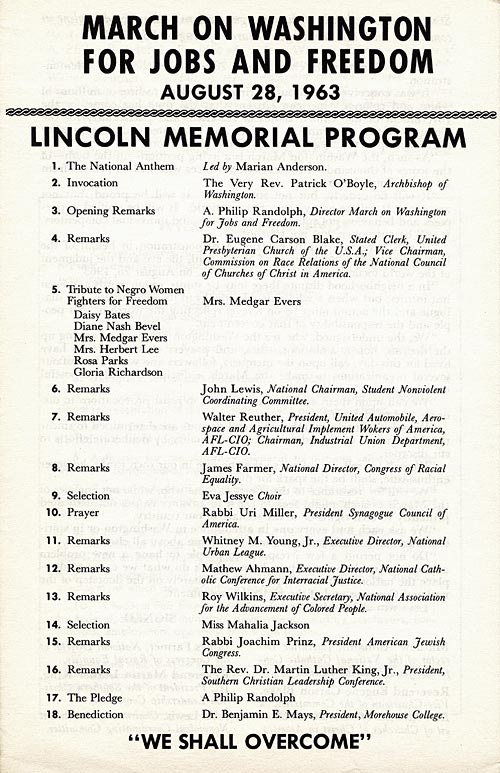

Martin Luther King, Jr., in his famous 1963 speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, used “join hands” with similar effectiveness:

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character … I have a dream that … one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

George Orwell, in his seminal essay, “Politics and the English Language,” illustrated the contrast between specific images and generalities by taking a well-known passage from Ecclesiastes:

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

and contrasting it with the same passage, rewritten in “modern English”:

Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

Orwell asks us, which is more expressive, as well as more beautiful?

Tonight, against all odds, we have grasped it. The future is in our hands. My friends, we have toppled a political dynasty.

Mamdani knows that a metaphorical image becomes all the more powerful the more you extend it. Here in this new paragraph he leans further into the metaphor with “grasped” and “in our hands.”

King, in his speech, employs a banking metaphor (“In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check”) for not just one but two paragraphs:

“When the architects of our Republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.)

I wish Andrew Cuomo only the best in private life. But let tonight be the final time I utter his name,

This got a well-deserved laugh from Mamdani’s audience. But there’s more here. This use of “let” sounds to me almost from a pulpit. King, ever the minister, uses “let” throughout his “Dream” speech:

“Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.”

“Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.”

And of course, “Let freedom ring.”

as we turn the page on a politics that abandons the many and answers only to the few. New York, tonight you have delivered. A mandate for change. A mandate for a new kind of politics. A mandate for a city we can afford. And a mandate for a government that delivers exactly that.

On January 1st, I will be sworn in as the mayor of New York City. And that is because of you. So before I say anything else, I must say this: Thank you. Thank you to the next generation of New Yorkers who refuse to accept that the promise of a better future was a relic of the past.

Mamdani is a master of contrast. Two paragraphs up we have many vs few; here we have future vs past.

You showed that when politics speaks to you without condescension, we can usher in a new era of leadership. We will fight for you, because we are you.

Or, as we say on Steinway, ana minkum wa alaikum.

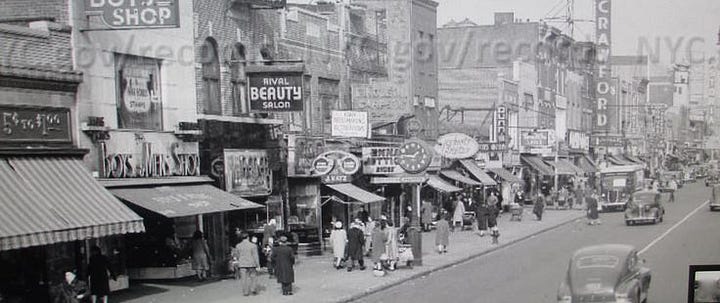

“Steinway” is a main shopping street in the heart of Astoria; Mamdani is its representative in the NY State Legislature. This is, once again, the use of a specific image. The Romans had a name for this kind of figure of speech (“synecdoche”) where a part is used to represent the whole.

Interestingly for New Yorkers, Astoria is traditionally associated with Greek-Americans, but the phrase here is Arabic, translated as, “I’m one of you, and I am for you.”

So here, the subtext of Astoria as a melting pot of different immigrant populations illustrates the surface message of “we are in this together.”

Thank you to those so often forgotten by the politics of our city, who made this movement their own. I speak of Yemeni bodega owners and Mexican abuelas. Senegalese taxi drivers and Uzbek nurses. Trinidadian line cooks and Ethiopian aunties. Yes, aunties.

“Thank you” is used here to tie together these paragraphs, which also creates an opportunity for segue.

“Auntie” feels evocative of Mamdani’s Ugandan roots.

Notice the specifics again, calling out a wide variety of nationalities and working-class jobs.

To every New Yorker in Kensington and Midwood and Hunts Point, know this: This city is your city, and this democracy is yours too. This campaign is about people like Wesley, an 1199 organizer I met outside of Elmhurst Hospital on Thursday night. A New Yorker who lives elsewhere, who commutes two hours each way from Pennsylvania because rent is too expensive in this city.

And now Mamdani calls out specific neighborhoods, three of them. My creative writing mentor, Susan Cheever, liked to point out that lists often have three items. She would say that with fewer than three, the reader may not get the generality the writer has in mind. (Note that in the prior paragraph, “X and Y” is done three times.)

Mamdani follows this with a specific example, beautifully painted in only two sentences, yet sufficient for us to get the point, and follows with another.

It’s about people like the woman I met on the Bx33 years ago who said to me, “I used to love New York, but now it’s just where I live.” And it’s about people like Richard, the taxi driver I went on a 15-day hunger strike with outside of City Hall, who still has to drive his cab seven days a week. My brother, we are in City Hall now.

Two more examples, making a total of three. And he ends on the important one, which also allows him to declare his kinship (“my brother”) with Richard, who is a stand-in here for the struggles of the working class.

This victory is for all of them. And it’s for all of you, the more than 100,000 volunteers who built this campaign into an unstoppable force. Because of you, we will make this city one that working people can love and live in again. With every door knocked, every petition signature earned, and every hard-earned conversation, you eroded the cynicism that has come to define our politics.

(Another triad: doors, petitions, conversations.)

Now, I know that I have asked for much from you over this last year. Time and again, you have answered my calls — but I have one final request. New York City, breathe this moment in. We have held our breath for longer than we know.

The idea of “breath” is used twice; it will be extended five-fold in the next paragraph. Again, recall King’s banking metaphor. And in some ways, breath is the more powerful of the two. The Greek term “psyche,” from which we get “psychology,” had a twin meaning: butterfly and soul, the idea being that breath, the animating force of life, was as if generated by a butterfly in one’s chest.

We have held it in anticipation of defeat, held it because the air has been knocked out of our lungs too many times to count, held it because we cannot afford to exhale. Thanks to all of those who sacrificed so much. We are breathing in the air of a city that has been reborn.

To my campaign team, who believed when no one else did and who took an electoral project and turned it into so much more: I will never be able to express the depth of my gratitude. You can sleep now.

To my parents, mama and baba: You have made me into the man I am today. I am so proud to be your son. And to my incredible wife, Rama, hayati: There is no one I would rather have by my side in this moment, and in every moment.

An article on Arabic terms of endearment says,

“The word ‘Hayati’ means ‘my life.’ This powerful term can be used for both romantic and familial relationships. It’s a way to express that the person is an essential part of your existence.”

The seemingly tiny gesture of this word says several things. First, Mamdani is not afraid to be who he is nor to show who he is. He is a Muslim and Arabic underlines that. Second, he follows the writing dictum: Trust the reader. You do not have to explain everything. The listener gets the sense of the word even though most won’t have ever heard it before. And third, he knows he is speaking/writing for the ages. Those who care enough will find out the exact definition of the word at some future point.

To every New Yorker — whether you voted for me, for one of my opponents, or felt too disappointed by politics to vote at all — thank you for the opportunity to prove myself worthy of your trust. I will wake each morning with a singular purpose: to make this city better for you than it was the day before.

Once again, we have a beautiful synecdoche extended and contrasted (“each morning” and “the day before”).

And he’s not afraid to make a general promise without first releasing 100 white papers. Unlike Trump (“I will fix it”), he has specific proposals in mind, but the audience is familiar with them, and this — an acceptance speech — is not the place for a detailed discussion of them. (He will call three of them out, in a single sentence, further down.)

And unlike Trump, he plans to be the mayor of all, not just those who voted for him. In fact, he will even serve those who didn’t vote at all; furthermore, rather than condemn them, he understands and sympathizes with the nonvoters.

There are many who thought this day would never come, who feared that we would be condemned only to a future of less, with every election consigning us simply to more of the same.

And there are others who see politics today as too cruel for the flame of hope to still burn. New York, we have answered those fears.

King, in his speech, never uses a metaphor only once. The second use, always in the same sentence, keeps the first from being an empty cliché. Referring to the Emancipation Proclamation, King says, “It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.” Indeed, King also uses, in the same paragraph, the same metaphor as Mamdani: “This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.”

And then, still in the same paragraph, King does it three more times, with three different metaphors:

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.

Tonight we have spoken in a clear voice. Hope is alive. Hope is a decision that tens of thousands of New Yorkers made day after day, volunteer shift after volunteer shift, despite attack ad after attack ad. More than a million of us stood in our churches, in gymnasiums, in community centers, as we filled in the ledger of democracy.

And while we cast our ballots alone, we chose hope together. Hope over tyranny. Hope over big money and small ideas. Hope over despair. We won because New Yorkers allowed themselves to hope that the impossible could be made possible. And we won because we insisted that no longer would politics be something that is done to us. Now, it is something that we do.

Every sentence here contains a contrast. (One of them has a contrast within a contrast!) And the final one is the most powerful, in that Mamdani is saying that the passive has become active. He did this earlier as well, e.g. “These are not hands that have been allowed to hold power … yet … you have dared to reach for something greater.”

Standing before you, I think of the words of Jawaharlal Nehru: “A moment comes, but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

Tonight we have stepped out from the old into the new. So let us speak now, with clarity and conviction that cannot be misunderstood, about what this new age will deliver, and for whom.

This will be an age where New Yorkers expect from their leaders a bold vision of what we will achieve, rather than a list of excuses for what we are too timid to attempt. Central to that vision will be the most ambitious agenda to tackle the cost-of-living crisis that this city has seen since the days of Fiorello La Guardia: an agenda that will freeze the rents for more than two million rent-stabilized tenants, make buses fast and free, and deliver universal child care across our city.

Like the call-out to Debs, Mamdani’s reference to La Guardia is intentional. He’s telling us which of his mayoral predecessors he most admires and most wants to be like. With massive construction projects, social programs, and employment programs, La Guardia was enacting a local version of FDR’s New Deal. Like La Guardia, Mamdani is not afraid to think big.

Years from now, may our only regret be that this day took so long to come. This new age will be one of relentless improvement. We will hire thousands more teachers. We will cut waste from a bloated bureaucracy. We will work tirelessly to make lights shine again in the hallways of NYCHA developments where they have long flickered.

After a couple of general claims, Mamdani’s third has great specificity. NYCHA, the NYC Housing Authority, is the landlord for New York’s public housing projects, famous for spawning rap stars and infamous for their squalid living conditions.

Safety and justice will go hand in hand as we work with police officers to reduce crime and create a Department of Community Safety that tackles the mental health crisis and homelessness crises head on. Excellence will become the expectation across government, not the exception. In this new age we make for ourselves, we will refuse to allow those who traffic in division and hate to pit us against one another.

In this moment of political darkness, New York will be the light. Here, we believe in standing up for those we love, whether you are an immigrant, a member of the trans community, one of the many Black women that Donald Trump has fired from a federal job, a single mom still waiting for the cost of groceries to go down, or anyone else with their back against the wall. Your struggle is ours, too.

And we will build a City Hall that stands steadfast alongside Jewish New Yorkers and does not waver in the fight against the scourge of antisemitism. Where the more than one million Muslims know that they belong — not just in the five boroughs of this city, but in the halls of power.

Even as he extends a hand to Jewish communities that felt alienated by his campaign, he doubles down on his Islamic heritage. In fact, by having the next sentence also refer to it, he’s giving it greater weight. (In a speech, indeed in all writing, more words equals greater importance.)

To me, Mamdani is saying, “I’m not going to back away from my heritage just to make you feel less threatened, because the threat is only in your own mind.”

No more will New York be a city where you can traffic in Islamophobia and win an election. This new age will be defined by a competence and a compassion that have too long been placed at odds with one another.

We will prove that there is no problem too large for government to solve, and no concern too small for it to care about.

I love this sentence. It’s the culmination of all the contrasts that came before it.

For years, those in City Hall have only helped those who can help them. But on January 1st, we will usher in a city government that helps everyone.

Again, Mamdani assures us he will be a mayor for all of us. His will be, to quote another great speaker whose speeches I use in my class, “a government of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Now, I know that many have heard our message only through the prism of misinformation. Tens of millions of dollars have been spent to redefine reality and to convince our neighbors that this new age is something that should frighten them. As has so often occurred, the billionaire class has sought to convince those making $30 an hour that their enemies are those earning $20 an hour.

Again, uniting instead of dividing.

They want the people to fight amongst ourselves so that we remain distracted from the work of remaking a long-broken system. We refuse to let them dictate the rules of the game anymore. They can play by the same rules as the rest of us.

Together, we will usher in a generation of change. And if we embrace this brave new course, rather than fleeing from it, we can respond to oligarchy and authoritarianism with the strength it fears, not the appeasement it craves.

After all, if anyone can show a nation betrayed by Donald Trump how to defeat him, it is the city that gave rise to him. And if there is any way to terrify a despot, it is by dismantling the very conditions that allowed him to accumulate power.

This is not only how we stop Trump; it’s how we stop the next one. So, Donald Trump, since I know you’re watching, I have four words for you: Turn the volume up.

“Donald, you are old and hard of hearing, literally and figuratively. You are disconnected from the city and the nation of your birth. Listen to your city cheer me instead of you.”

We will hold bad landlords to account because the Donald Trumps of our city have grown far too comfortable taking advantage of their tenants.

Trump’s real-estate mogul father, Fred Trump, built middle-class housing for the post-war generation. Donald went into his father’s business before going off on his own (financed by his father’s money). He and his father discriminated against black applicants in the 1960s and 1970s, a crime they were prosecuted for.

We will put an end to the culture of corruption that has allowed billionaires like Trump to evade taxation and exploit tax breaks. We will stand alongside unions and expand labor protections because we know, just as Donald Trump does, that when working people have ironclad rights, the bosses who seek to extort them become very small indeed.

New York will remain a city of immigrants: a city built by immigrants, powered by immigrants and, as of tonight, led by an immigrant.

So hear me, President Trump, when I say this: To get to any of us, you will have to get through all of us.

This is a twist on the usual “to get to you, they will have to go through me.” In Mamdani’s version, we stand together to defend each and every one of us.

When we enter City Hall in 58 days, expectations will be high. We will meet them. A great New Yorker once said that while you campaign in poetry, you govern in prose.

The great New Yorker was Mario Cuomo, three-term Governor of New York, who indeed was ten times the politician, and a hundred times the man, that Andrew is.

If that must be true, let the prose we write still rhyme, and let us build a shining city for all.

The “shining city on a hill” was a signature phrase of Ronald Reagan’s, though “city on a hill” goes back to the New Testament and first became synonymous with American exceptionalism when Puritan John Winthrop used the phrase in an 1630 sermon.

And we must chart a new path, as bold as the one we have already traveled. After all, the conventional wisdom would tell you that I am far from the perfect candidate.

I am young, despite my best efforts to grow older. I am Muslim. I am a democratic socialist. And most damning of all, I refuse to apologize for any of this.

Mamdani could hardly be more different from Trump, or, for that matter, Reagan, who in his day was America’s oldest president and its least socialist.

And yet, if tonight teaches us anything, it is that convention has held us back. We have bowed at the altar of caution, and we have paid a mighty price. Too many working people cannot recognize themselves in our party, and too many among us have turned to the right for answers to why they’ve been left behind.

Is this an oblique reference to Chuck Schumer and the DNC? I suspect it is. And, in the modern era, the first working people to have turned to the right for answers were the so-called Reagan Democrats.

And could there be a better indication that the DNC is on the wrong side of history than this headline:

“CNN Democratic strategists David Axelrod and Van Jones left stunned by Mamdani’s victory speech: ‘The tone was off’.”

Perhaps even worse was their objection:

“Mamdani, who barely cracked 50 percent in his win, eschewed a call for unity, as is traditional after a contentious race, and instead leaned into an at-times thumping victory lap,” leaving CNN’s panel a bit stunned

The speech was entirely about unity. That they couldn’t hear it leaves me more than a bit stunned.

We will leave mediocrity in our past. No longer will we have to open a history book for proof that Democrats can dare to be great.

Our greatness will be anything but abstract. It will be felt by every rent-stabilized tenant who wakes up on the first of every month knowing the amount they’re going to pay hasn’t soared since the month before. It will be felt by each grandparent who can afford to stay in the home they have worked for, and whose grandchildren live nearby because the cost of child care didn’t send them to Long Island.

It will be felt by the single mother who is safe on her commute and whose bus runs fast enough that she doesn’t have to rush school drop-off to make it to work on time. And it will be felt when New Yorkers open their newspapers in the morning and read headlines of success, not scandal.

Each of the three big campaign promises — free buses, rent freezes for two million New Yorkers, and free child care — is concretized in hypothetical examples.

Most of all, it will be felt by each New Yorker when the city they love finally loves them back.

Together, New York, we’re going to freeze the… [rent!] Together, New York, we’re going to make buses fast and… [free!] Together, New York, we’re going to deliver universal… [child care!]

Let the words we’ve spoken together, the dreams we’ve dreamt together, become the agenda we deliver together. New York, this power, it’s yours. This city belongs to you.

Thank you.

The idea of returning power to the voters, to the citizenry, is a powerful one, and utterly necessary if Trump is to be limited to a presidency instead of a regime. And if it is to start at the local level, what better place than the nation’s largest city?

I'm disappointed but not surprised by 70-year-old Axelrod's response that Mamdani's inspiring speech didn't sound unifying enough. Axelrod's memoir is subtitled "My 40 years in politics," which says it all. Thank you for your service. Now shut up.

CNN like other corporate legacy media is responsible to its stockholders. Mamdani and his voters are gloriously not.

Do you think ZM wrote the speech himself? If yes, I'll send a thank-you note to Bronx Science and Bowdoin College.

Inspiring speech, insightful analysis.