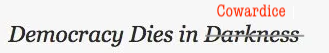

Someone get Jeff Bezos a copy of Timothy Snyder’s latest book

Bezos fundamentally misunderstands the concept of freedom — unless he’s just a scared little greedy liar

Jeff Bezos is an ultra-billionaire terrified of being shut out of government contracts, especially in businesses where he competes with Elon Musk, who not only has the inside track, but is sociopathic enough to earn the continued respect of our Sociopath-in-Chief. Terror is a form of weakness, and Bezos’s kowtowing has been embarrassing to watch.

Bezos’s shift to the right began with the hiring of Will Lewis, late of the Wall Street Journal, who quickly installed a bunch of right-wing-newspaper cronies there. (That’s when I terminated my subscription.) He took another right turn by nixing an editorial endorsing Harris in the 2024 election. (That’s when a few hundred thousand more subscribers fled.)

He’s now entering the Murdoch zone. Here’s the news, as reported by Deadline:

Jeff Bezos is exerting more influence over the content of The Washington Post opinion pages, as he announced that the editorials will now focus on “defense of two pillars: personal liberties and free markets.”

But Bezos also made clear that alternate views will not appear on the pages.

“We’ll cover other topics too of course, but viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others,” Bezos wrote in a memo to staffers this morning.

First, Bezos is smart enough to know that this isn’t a wise business move for the Post, though he’s pretending otherwise.

Bezos wrote in his note, “We are going to be writing every day in support and defense of two pillars: personal liberties and free markets. We’ll cover other topics too of course, but viewpoints opposing those pillars will be left to be published by others.

“There was a time when a newspaper, especially one that was a local monopoly, might have seen it as a service to bring to the reader’s doorstep every morning a broad-based opinion section that sought to cover all views. Today, the internet does that job.

When it comes to writing every day in support of personal liberties and free markets, you know who else does that job, Jeff? The Wall Street Journal. When Bezos started Amazon, he didn’t just try to become another Walmart. So something unrelated to business is going on here. Or, more accurately, something related to Bezos’s broader business interests is involved here. (There’s the way Bezos’s data and space businesses need government contracts. And Deadline rightly reminds us that Amazon is currently being sued for antitrust violations.)

But more important is the way Bezos fundamentally misunderstands, or at least misrepresents, freedom.

“I am of America and for America, and proud to be so. Our country did not get here by being typical. And a big part of America’s success has been freedom in the economic realm and everywhere else. Freedom is ethical — it minimizes coercion — and practical — it drives creativity, invention, and prosperity.”

Timothy Snyder’s new book, On Freedom, is a critique of exactly this sort of conception of freedom. I should say, I don’t think this is his best book, in fact, it’s easily his worst as a piece of writing. It feels like something he felt he had to write. It has none of the passion of Bloodlands or Black Earth; for policy-ideas-cum-memoir, Our Malady is far superior; in terms of cultural influence, On Tyranny will be foremost in Synder’s legacy.

But On Freedom offers an important corrective to the concept Bezos and his fellow plutocrats seem to share — and which arguably is broadly enough held to win the 2024 election for Trump.

Rupert Sparling describes the distinction in a book review in Stanford Humanities Today:

Synder thinks that the concept of freedom we encounter in our politics and culture tends to be “negative freedom.” According to this kind of freedom, in order to be free, we need to be free from the interference of government and from each other. When you can do as you please without interference, you’re free. That’s negative freedom.

But Snyder thinks negative freedom doesn’t really tell us much about how to promote freedom or how to create more free individuals. It fails to make any room for the conditions that allow for human beings to be free, and instead, focuses on human beings who are already fully set up, materially and psychologically, for freedom. For instance, negative freedom starts with fully-grown human beings who are already autonomous and capable of independent action, and then it demands that these human beings be left alone to do as they please. But how do they become adults? How do they become autonomous? And how do they become capable of independent action?

A better concept of freedom would answer these questions … While negative freedom focuses on abstract individuals outside of space and time, Snyder’s freedom starts from the kinds of creatures we are.

The distinction between these two ideas of freedom is hardly new. Robert Frank did an excellent job, in his book The Darwin Economy (Princeton University Press, 2011), of arguing that there is no personal liberty if we don’t do enough to support the common good. (Frank’s book is itself deeply grounded in John Stuart Mills’s On Liberty, which also argues for a synthesis of individual liberty and the commons.)

Barack Obama had much the same idea in mind when he made the statement that was famously quoted out of context by Mitt Romney and others. Here’s what Obama actually said:

Somebody helped to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Somebody invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a business — you didn’t build that. Somebody else made that happen. The Internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the Internet so that all the companies could make money off the Internet.

(Ironically, the pre-Bezos Washington Post was among the fact-checkers for “You didn’t build that.”)

Similarly, free markets don’t create themselves — they can only flourish when embedded in a culture of freedom and democracy. And left to their own devices, free markets never stay free. The same market forces that allocate goods and services efficiently, when left unchecked, inexorably become oligopolies, trusts, and monopolies.

Once in a while, innovation is enough to overcome those forces, though usually only after a misstep by the oligarchs (e.g., Microsoft missing the shift from computers to smartphones, even though it was predicted 25 years earlier by its smartest senior fellow). Generally, only strong government oversight of markets keeps them free.

Snyder’s website has a nice one-paragraph summary of the basic point. If we could get Bezos to read even just this, perhaps it would make a dent in his greedy and self-serving misconceptions:

Freedom is the great American commitment, but as Snyder argues, we have lost sight of what it means—and this is leading us into crisis. Too many of us look at freedom as the absence of state power: We think we’re free if we can do and say as we please, and protect ourselves from government overreach. But true freedom isn’t so much freedom from as freedom to—the freedom to thrive, to take risks for futures we choose by working together. Freedom is the value that makes all other values possible.

Today's extended featured opinion piece in the WaPo rebukes the Bezos directive: "Here’s the real threat to ‘personal liberties and free markets:' The rapidly spreading authoritarianism coming from this administration threatens all of our freedoms." by Dana Millbank. Could angrily calling out the lawlessness of the Musk purge, impending trade wars and the end of DEI be what Bezos had in mind? As long as an individual opinion writer speaks this kind of truth to power, I will keep my subscription.